[ad_1]

In the heart of the bustling city of Barcelona is a square that at first sight seems like an oasis of calm. The Plaza del Sol, as the name suggests, is a suntrap and the perfect place to while away a few hours.

|

|

The plaza is great for hanging out – but residents could not sleep

|

The problem is that the square is just too popular and for many of the city’s young inhabitants has become the number one venue to meet friends and hang out until the small hours.

One resident said it was like living in a permanent party.

Even the shops around the square reflect its reputation for late-night carousing, selling beer, pizza and little else.

The situation had become unbearable for those with apartments around the square, who have lived with unacceptable noise levels for the past 20 years.

Step in Barcelona’s fabrication laboratory, one of a network of 1,200 workshops around the world that allow people to test out new designs and ideas, and build products and new technology using a range of cutting-edge tools. Labs share their designs online so that something built in Boston can be replicated in a lab in Shenzhen.

With the help of some EU money, the lab built low-cost, easy-to-use sensors that can detect air pollution, noise levels, humidity and temperature.

“This was not only about being part of a scientific project but about enabling political action,” said Tomas Diez, who runs the lab.

|

|

Residents used the sensors to prove how high noise levels were getting

|

Families placed the sensors on their balconies and were able to demonstrate that night-time noise levels – with peaks of 100 decibels – were far higher than World Health Organization recommendations.

Armed with this information, the residents went to the city council, pressing them to rethink the use of the plaza.

Police now move people on at 23:00. Rubbish lorries, which had previously cleared up when the partygoers left in the early hours, have been rescheduled for the morning, and steps that provided seating for gatherers have now been filled with plant boxes.

“Now the square is not just for people who want to party at night,” said Mr Diez.

His vision for fab labs goes further, imagining them as a vehicle to allow cities to become truly self-sufficient. They can provide its citizens with technology to grow their own food, 3D-print new products whenever they need them and offer them the tools they need to fight the growing problems of urbanism.

He, along with other technologists, designers and architects, is backing a project known as Fab City – a collective of 18 cities from Europe, India, China and America – that aims to create more sustainable and productive cities around the world in the next 30 years.

The vision is partly idealistic, harking back to pre-Industrial Revolution days when people made their own clothes and goods and shopped locally.

But it is also about improving the environment, moving from a globalised world where goods are shipped from China in huge container ships to a place where people can pick up a blueprint from a fab lab and create products in their own city.

“We are trying to build a new productivity model for society, creating a new sustainable economy in cities where people can prototype and test ideas,” said Mr Diez.

The data collection in Barcelona was part of an EU project – Making Sense – that aims to empower citizens through “personal digital manufacturing”.

It is part of a wider attempt to rethink smart cities and put control back firmly in the hands of citizens.

“We wanted to end this top-down approach where cities go to companies and ask them to build infrastructure and then pretend that is a smart city,” said Mr Diez.

And along the way, he hopes to build a new type of digital economy, one in which citizens own and control their own data – what he calls “citizen-based infrastructure”.

Giving teenagers a say

It is not just fab labs that are hoping to use data to empower people.

Sensors in a Shoebox was a project set up earlier this year in Detroit, aiming to give local teenagers a say in urban planning.

The project provides compact sensor kits that allowed the children to collect a range of data from two different locations – one on the waterfront and the other in a local park.

|

|

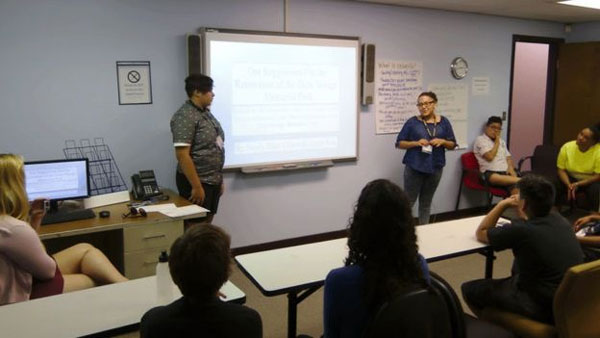

Teenagers in Detroit learned about the benefits – and limitations – of sensor technology — PHOTO: MICHIGAN PHOTOGRAPHY

|

“We took the view that we can’t have smart, connected cities without smart and connected young people,” said Elizabeth Moje, dean of the school of education at the University of Michigan, which headed up the project.

Air quality was important to the teens – a personal issue for many in a city where one in six residents lives with asthma.

The children also learned the limitations of data collection.

While they were able to measure the number of people who used a certain area, they also had to go out and see for themselves what type of person used the area, explained Prof Moje.

“If there were more elderly people, you might want more benches – if there were young children, more play areas,” she said.

“The youngsters learned that a piece of technology can’t answer every question.”

It was also important that the children saw that the data they collected and the observations they had made could have an impact on city planning.

Their recommendations were passed on to representatives from the mayor’s office, community groups and Citizen Detroit.

“We have to teach children to be critical thinkers, as well as how to be good and productive citizens. This enabled them to learn about their communities, even if they don’t go on to be engineers or social scientists,” said Prof Moje.

|

|

One of the youngsters’ recommendations was that more benches needed to be put in shade in a local park — Photo: SENSORS IN A SHOEBOX

|

Dr Jennifer Gabrys leads the Citizen Sense project at Goldsmiths, University of London, which aims to research how effective citizen-led sensor projects are.

Giving people the tools to collect their own data can sometimes be a “perfunctory gesture to make smart city projects more palatable”, she said.

“Cities increasingly have so many sensors generating so much data, some of which people have access to and some of which they don’t.

“People may not want everything monitored and who decides and shapes this agenda is a big question for future urban democracy.”

Source: BBC

[ad_2]

Source link