[ad_1]

Less than a decade ago, doctors in Australia believed they were close to eliminating syphilis from remote indigenous communities – the centre of national efforts to fight the disease.

Since then, however, the sexually transmitted infection has grown into an outbreak spanning three states and a territory.

Doctors say six babies have died from congenital syphilis since 2011.

During the same period, they say the outbreak overwhelmingly affecting indigenous Australians has risen from about 120 people to more than 2,100.

Health experts have characterised it as a crisis, saying the nation faces a “big task” to bring the problem under control.

How did this happen?

The majority of syphilis sufferers in Australia are young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who live in regional areas in the nation’s north and centre, doctors say.

Indigenous health experts, including Associate Prof James Ward, issued a call in the Medical Journal of Australia in 2011 to try to end syphilis in communities where it was a problem.

|

|

Syphilis is now a problem in (clockwise from bottom) South Australia, Western Australia, Northern Territory and Queensland — Photo: SA HEALTH AND MEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE

|

But Associate Prof Ward says it has instead “spiralled out of control”, spreading from one Queensland community to elsewhere in the state, as well as to the Northern Territory, Western Australia and South Australia.

Why the outbreak has happened is not fully understood, although experts say it can partly be attributed to people moving in and out of communities.

But it has been worsened by authorities’ failure to adequately respond, according to Associate Prof Ward, from the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute.

“If this had occurred among young, heterosexual people in non-indigenous Australia there would be a national outcry,” he told the BBC.

“We missed the opportunity to bring it under control. It’s a really poor indictment on the public health response.”

Problem enters cities

The Australian government has described the problem as unacceptable, conceding it has taken too long to respond.

“In a day and age like ours, when you hear that you think: What the hell has happened? How was this situation allowed to happen?'” Indigenous Health Minister Ken Wyatt told Australian Broadcasting Corporation earlier this month.

In Queensland, home to more than half of recorded cases, the state government in 2016 pledged A$15m (£8.5m, $11m) towards tackling the problem.

It has placed much blame over the issue on funding cuts by a previous state government administration.

Last year, Canberra launched a A$8m emergency response plan to boost medical supplies to remote communities.

But experts fear it may be too late, with the disease already infiltrating Queensland cities such as Cairns and Townsville.

“In a small community, you’re able to contain the problem more easily by keeping track of those affected,” said Cairns Sexual Health Service director Dr Darren Russell.

“But here in the city, we’re actually feeding the problem. There are people coming in and going out all the time, you can’t keep track of everyone. The disease becomes self-sustaining.”

‘Ashamed’ to seek help

The government’s emergency response includes new advertising campaigns, and tools such as testing kits to treat patients more quickly. The first kits were distributed last week.

However, health workers say progress is often hindered by a social stigma around the disease.

Convincing sufferers just to get treated can be hard, says Marion Norrie, an Aboriginal health worker in northern Queensland. She says she has helped children as young as 12.

|

|

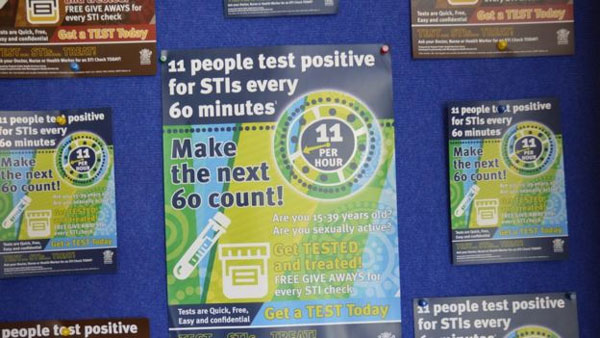

Campaigns aim to raise awareness of STI testing Photo: WUCHOPPEREN HEALTH SERVICE

|

“The biggest thing we find is that when someone has tested positive for syphilis, they are so ashamed they don’t even want to come into the clinic,” she told the BBC.

This was despite treatment often being as simple as a jab of penicillin, she said.

“We had one young girl who just would not even get out of the car,” Ms Norrie said.

“We tried to go and treat her in the car and she flat out refused to have the injections. So she’s still out there… and the cycle just goes on.”

‘Plenty to be done’

Associate Prof Ward said it remained too early to assess the impact of the most recent response.

However he believed that awareness campaigns were making a difference, and that care for pregnant women had improved.

There had been no recent cases of congenital syphilis – a “very good sign”.

“There’s still plenty that needs to be done,” he said. “We need to try and bring it under control over the next while and that is a very big task.”

Source: BBC

[ad_2]

Source link